The 'Empathy Deficit' Myth in Neurodiverse Unions

Re-evaluating Emotional Reciprocity in ASD/NT Marriages

Executive Summary

The prevailing clinical and cultural narrative surrounding

marriages between neurotypical (NT) individuals and partners with Autism

Spectrum Disorder (ASD) has historically been dominated by the "empathy

deficit" model. This reductionist paradigm posits that the primary source

of relational discord in these unions stems from the autistic partner's

inherent, pathological inability to experience or demonstrate empathy. This

report challenges that view through a comprehensive synthesis of contemporary

neuroscientific research, sociological theory, and clinical observation.

By deconstructing the monolithic concept of empathy into its

cognitive and affective components, the analysis reveals that while autistic

individuals may struggle with cognitive perspective-taking (Theory of Mind),

their capacity for affective empathy—feeling what others feel—is often intact

or even heightened. Furthermore, the introduction of the "Double

Empathy Problem" reframes relational breakdown not as a one-sided deficit

but as a bidirectional failure of mutual understanding between two distinct

neurotypes.

This report extensively examines the friction points in

ASD/NT marriages, including the phenomenon often labeled "Cassandra

Syndrome," the impact of alexithymia, and the misinterpretation of

autistic behaviors such as shutdowns and "systemizing" as

indifference. Finally, it provides an exhaustive overview of neuro-affirming

therapeutic interventions, communication scripts, and alternative "love

languages" (e.g., parallel play, penguin pebbling) that bridge the

neurological divide, moving beyond the myth of the empathy deficit toward a

model of cross-cultural translation and mutual accommodation.

1. Deconstructing the Empathy Construct in Autism

To understand the dynamics of an ASD/NT marriage, one must

first dismantle the clinical oversimplification that "autistic people lack

empathy." Empathy is not a singular neurological function but a

multidimensional construct comprising at least two distinct systems: cognitive

empathy and affective (emotional) empathy. Research indicates that the deficits

observed in autism are highly specific and often compensatory rather than

absolute.

1.1 The Dissociation of Cognitive and Affective Empathy

Cognitive empathy, often equated with "Theory of

Mind" (ToM), refers to the intellectual ability to identify and understand

another person's mental state—to "read" intentions or thoughts

without necessarily sharing the emotional state. Affective empathy, conversely,

is the visceral, emotional response to another’s state—feeling sadness when

someone cries or distress when they are in pain.

Research utilizing the Basic Empathy Scale (BES) and various

neuroimaging tasks has consistently demonstrated a dissociation between these

two faculties in autistic adolescents and adults. Studies indicate that while

individuals with ASD frequently score lower on measures of cognitive

empathy—struggling to intuit what a partner is thinking based on subtle

cues—their scores for affective empathy often mirror those of neurotypical

control groups.

In the context of marriage, this dissociation explains a

common, painful dynamic: the autistic partner may not intuitively know (cognitive)

that their spouse is upset because they missed the non-verbal signifiers, but

once the emotion is explicitly communicated, they feel (affective)

a deep, often overwhelming sense of concern. The "deficit" is

not in the caring, but in the data acquisition.

1.1.1 The Valence-Specific Deficit

Nuanced research reveals that the empathy profile in autism

is even more specific. Adolescents with ASD have been shown to empathize

effectively with positive emotions but struggle specifically with negative

emotional valence. In a marriage, this means an autistic spouse might

readily share in their partner's joy or excitement but fail to mirror or

process sadness or anger appropriately. This is not necessarily due to

callousness but may stem from a difficulty in processing negative affect, which

can trigger a defensive withdrawal or "shutdown" to manage the

intensity of the negative stimulus.

1.1.2 The Empathy Imbalance Hypothesis

The Empathy Imbalance Hypothesis (EIH) proposes that

individuals with autism may actually possess a surplus of

affective empathy combined with a deficit in cognitive empathy. This

imbalance can lead to a state of chronic hyperarousal. When an autistic partner

witnesses their spouse in distress, they may feel the emotion so intensely that

it becomes unmanageable. Without the cognitive tools to regulate this influx or

understand its precise cause, they may withdraw to self-regulate. The

neurotypical partner, observing this withdrawal, interprets it as coldness or a

lack of empathy, when in reality, it is a protective mechanism against an

excess of empathy.

1.2 The Role of Alexithymia as a Confounding Variable

A critical error in previous relationship research has been

the conflation of autism with alexithymia. Alexithymia is a subclinical

personality trait characterized by a difficulty in identifying, describing, and

processing one's own emotions.

While alexithymia is highly comorbid with autism (estimates

suggest approximately 50% of autistic individuals have alexithymia), it is a

distinct condition. Research suggests that the "empathy

deficits" traditionally attributed to autism are often better explained by

co-occurring alexithymia.

In an ASD/NT marriage, an autistic partner with high

alexithymia may struggle to empathize not because they are autistic, but

because they cannot recognize the physiological signals of emotion within

themselves. If one cannot identify "sadness" in one's own body

(distinguishing it from hunger, fatigue, or general malaise), one cannot

simulate or understand that state in a partner. This "blindness"

to internal states leads to a breakdown in the mirroring process required for

emotional reciprocity.

However, neuroimaging data indicates that when controlling

for alexithymia, the neural circuits associated with empathy in autistic

individuals function similarly to those in neurotypicals. This distinction

is vital for therapeutic intervention: if the issue is alexithymia, the

treatment should focus on interoception and emotional labeling, rather than

social skills training.

1.3 Practical vs. Emotional Empathy

The literature distinguishes between the internal experience

of empathy and the external demonstration of it. Autistic partners often

default to "practical empathy" or "systemizing empathy."

Instead of offering verbal reassurance or physical affection (neurotypical

standards for empathy), an autistic partner may attempt to "fix" the

problem causing the distress.

For example, if an NT wife is distressed about a difficult

day at work, she may seek validation ("That sounds terrible, I'm so

sorry"). The autistic husband, operating through a systemizing lens, may

view the distress as a problem to be solved and offer logistical advice

("You should speak to HR or adjust your schedule"). To the NT

partner, this feels dismissive and clinically detached. To the Autistic

partner, this is the highest form of care—expending cognitive energy to remove

the source of the loved one's pain. This mismatch in the language of

empathy, rather than the presence of empathy, is the seed of

the "Double Empathy Problem."

2. The Double Empathy Problem in Romantic Relationships

The "Double Empathy Problem," coined by Dr. Damian

Milton, represents a paradigm shift in understanding autistic social

interaction. It posits that social difficulties are not solely the result of

autistic deficits but arise from a bidirectional disconnect between two

different neurotypes.

2.1 The Fallacy of the Sole Deficit

Traditional models, such as Theory of Mind, placed the

burden of communication entirely on the autistic individual. The assumption was

that NT communication is "correct" and autistic communication is

"disordered." The Double Empathy Problem argues that while autistic

people struggle to understand NT social cues, NT people are equally inept at

interpreting autistic social cues.

In a mixed-neurotype marriage, this manifests as a mutual

failure of insight. The NT partner may accuse the autistic partner of

"lacking social insight" into neurotypical culture, yet the NT

partner rarely questions their own lack of insight into autistic

culture.

2.2 Cross-Cultural Misunderstandings

Milton suggests viewing ASD/NT relationships through the

lens of a cross-cultural exchange. Just as two people from vastly

different cultures may struggle to read each other's gestures or implied

meanings without harboring ill will, neurodiverse couples often speak different

emotional languages.

Research supports this: autistic individuals often find it

easier to empathize with and understand other autistic individuals. This

"type-matched" ease of communication suggests that the deficit is

relational, not intrinsic. In an ASD/NT marriage, the friction arises because

the NT partner expects the Autistic partner to simulate a neurotypical brain,

while the Autistic partner is often exhausted by the effort of

"masking" to meet these expectations.

2.3 The Impact of Masking on Intimacy

Masking—the conscious or unconscious suppression of autistic

traits to fit in—is a significant barrier to intimacy. An autistic partner may

spend their entire workday masking to survive socially and professionally. When

they return home, they may be in a state of exhaustion or "autistic

burnout," leading to a drop in the mask.

If the marriage relies on the autistic partner "acting

neurotypical" (making eye contact, engaging in chit-chat, suppressing

stims), the home becomes another workplace rather than a sanctuary. When the

mask inevitably slips, the NT partner may feel they are seeing a "Jekyll

and Hyde" transformation, interpreting the unmasked autistic state as

withdrawal or lack of effort, rather than a return to a baseline neurological

state.

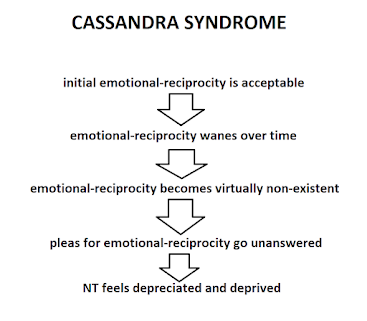

3. The "Cassandra Syndrome" and Relational

Trauma

The concept of "Cassandra Syndrome" (also known as

Cassandra Affective Deprivation Disorder or CADD) is central to the discourse

on ASD/NT marriages, particularly those involving neurotypical women and

autistic men. It describes a state of emotional deprivation and psychological

distress experienced by the NT partner, compounded by a lack of validation from

the outside world.

3.1 Origins and Definition

Coined by counselor Maxine Aston, the term references the

Greek mythological figure Cassandra, who was given the gift of prophecy but

cursed so that no one would believe her. In the context of neurodiverse

relationships, the NT partner often experiences their autistic spouse as

emotionally unavailable or damaging behind closed doors, while the spouse

appears charming, intelligent, and "normal" to the outside

world.

The syndrome is characterized by:

- Loneliness

and Isolation: A profound sense of being alone despite being

married.

- Self-Doubt: Questioning

one’s own sanity or perception of reality due to the partner's denial or

lack of reciprocity.

- Physical

and Mental Health Decline: Anxiety, depression, and

stress-related somatic symptoms.

3.2 The Controversy and Neuro-Affirming Critiques

While "Cassandra Syndrome" has provided a vital

framework for validating the pain of NT partners, it is highly controversial

within the neurodiversity community and is not a recognized diagnosis in the

DSM-5.

Critics argue that the concept:

- Pathologizes

the Autistic Partner: It frames the autistic partner as the

perpetrator of "deprivation" and the NT partner as the victim,

ignoring the bidirectional nature of the communication

breakdown.

- Promotes

Deficit Models: It relies on the assumption that the autistic

partner lacks empathy, rather than expressing it

differently.

- Weaponization: In

some instances, the label is used to absolve the NT partner of

responsibility for their own communication style, casting the autistic

partner's natural traits (e.g., need for solitude) as abusive

"withholding".

3.3 Ongoing Traumatic Relationship Syndrome (OTRS)

A more clinical and less blaming framework is "Ongoing

Traumatic Relationship Syndrome" (OTRS). This perspective acknowledges

that the dynamic itself is traumatizing. The NT partner’s need

for emotional attunement is repeatedly unmet, triggering an attachment panic.

Simultaneously, the Autistic partner’s need for sensory regulation and clarity

is repeatedly violated by the NT partner’s emotional intensity, triggering a

nervous system freeze or flight response.

The cycle typically follows a pattern:

- Pursuit: The

NT partner seeks emotional connection (often verbally or through

proximity).

- Overwhelm: The

Autistic partner experiences this demand as sensory or cognitive overload.

- Withdrawal: The

Autistic partner shuts down or creates distance to regulate.

- Trauma: The

NT partner experiences the withdrawal as rejection/abandonment; the

Autistic partner experiences the pursuit as an

attack/intrusion.

3.4 Misinterpreting Shutdowns vs. The Silent Treatment

A critical distinction in these relationships is the

difference between an "autistic shutdown" and the "silent

treatment." To the NT observer, they look identical: the partner stops

speaking, avoids eye contact, and withdraws. However, the intent and mechanism

are opposite.

- The

Silent Treatment: A manipulative, conscious choice to withhold

communication to punish the partner or gain leverage.

- Autistic

Shutdown: An involuntary neurological response to sensory or

emotional overload. The brain's processing capacity is exceeded, and

speech centers may temporarily go offline. The individual cannot speak,

even if they want to.

When an NT partner interprets a shutdown as the silent

treatment, they often escalate their attempts to get a response ("Why are

you ignoring me? Answer me!"). This increases the cognitive load on the

autistic partner, deepening the shutdown and prolonging the

disconnection.

4. Autistic Love Languages: Reframing Reciprocity

If the standard definition of empathy (verbal validation,

mirroring facial expressions) often fails in ASD/NT marriages, it is necessary

to identify the alternative channels through which autistic partners express

care. These "neurodivergent love languages" are often overlooked but

represent deep reservoirs of loyalty and affection.

4.1 Penguin Pebbling

Derived from the behavior of Adélie penguins who present

pebbles to their mates, "Penguin Pebbling" in the autism community

refers to the gifting of small, sometimes seemingly insignificant items (a cool

rock, a meme, a link to an article).

Unlike traditional gift-giving, which is often tied to

occasions, pebbling is associative. The autistic partner sees an object, links

it to the partner, and presents it as a token of that mental link ("I saw

this and thought of you"). It is a tangible demonstration of cognitive

empathy—proof that the partner occupies space in the autistic person's

mind. NT partners often miss the significance of these gestures if they

are expecting grander or more conventional displays of affection.

4.2 Parallel Play and Body Doubling

"Parallel play," a concept usually applied to

toddlers, is a sophisticated form of intimacy for autistic adults. It involves

being in the same room as the partner, engaged in separate activities (e.g.,

one reading, one gaming), without direct interaction.

For an autistic individual, whose social battery drains

quickly, the desire to be alone together is a profound

compliment. It signals that the partner is "safe" enough to be around

without the pressure of masking or performing. This is also known as "body

doubling," where the presence of another person provides a grounding effect. NT

partners often interpret this as "ignoring" them, missing the fact

that for the autistic partner, sharing space is the

interaction.

4.3 Infodumping as Intimacy

"Infodumping"—speaking at length about a special

interest—is often viewed by NT partners as self-centered monologuing. However,

within autistic culture, sharing knowledge is a primary love language. It is an

act of trust: "I am sharing the thing that brings me the most joy in the

world with you". It is an invitation into their inner world.

Rejection of the infodump ("I don't care about

trains/coding/history") is frequently experienced by the autistic partner

as a rejection of their core self.

4.4 Systemizing as Care (Acts of Service)

Baron-Cohen’s "Systemizing Mechanism" suggests

that autistic brains are tuned to input-operation-output relationships. In

relationships, this translates to "Acts of Service" on steroids. An

autistic partner may show love by optimizing the household: fixing the wi-fi,

reorganizing the pantry for efficiency, or researching the best car

insurance.

This is "logical empathy." The autistic partner

reasons: "My partner is stressed by X. If I fix X, they will be

happy." When the NT partner wants emotional validation ("Just listen

to me!"), the autistic partner’s attempt to fix the problem is an attempt

to remove the pain, not to dismiss the feelings.

4.5 Unwavering Loyalty and Honesty

Research suggests that autistic partners often bring high

levels of loyalty, reliability, and honesty to relationships. The lack of

social guile means that autistic partners are less likely to engage in

manipulation, deceit, or infidelity. They are often "what you see is what

you get." While their honesty can sometimes be perceived as bluntness, it

provides a stable foundation of trust for partners who learn to interpret it

not as cruelty, but as transparency.

5. Clinical Interventions: Bridging the Gap

Traditional couples therapy can be disastrous for

neurodiverse couples if the therapist relies on standard NT-centric models that

prioritize "emotional attunement" and "eye gazing" without

adapting for sensory and cognitive differences. Neuro-informed therapy focuses

on translation and structural accommodation.

5.1 Adapting the Gottman Method

The Gottman Method, a gold standard in couples therapy,

requires adaptation for ASD/NT pairs.

5.1.1 Love Maps

Gottman’s "Love Maps" involve knowing the

partner's inner world (friends, stresses, dreams). For autistic partners, the

open-ended nature of "How was your day?" can be paralyzing. Adapted

Love Maps use specific, data-driven questions.

- Standard: "Tell

me about your hopes."

- Adapted: "What

are the three projects you are most excited about this month?" or

"Who are the two colleagues causing you the most stress right

now?"

5.1.2 The Four Horsemen and Stonewalling

Gottman identifies "Stonewalling" (withdrawal) as

a predictor of divorce. However, in neurodiverse couples, stonewalling must be

differentiated from physiological shutdown. Therapists must teach

the couple to recognize the signs of sensory overwhelm. The intervention is not

to force the partner to stay in the conversation (which causes meltdowns) but

to establish a formalized "Time Out" signal with a guaranteed return

time.

5.2 Communication Scripts and Boundaries

Because implicit communication fails in these relationships,

explicit scripting is essential. Therapists help couples develop

"protocols" for common interactions.

5.3 Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT) Adaptations

EFT focuses on attachment bonds. For the autistic partner,

alexithymia can make identifying "attachment needs" difficult.

Therapists work to translate somatic sensations into emotional language.

- Therapist: "When

your wife raises her voice, what happens in your body?"

- Client: "My

chest gets tight and I want to run."

- Therapist: "That

tightness is fear. You are afraid of getting it wrong and hurting

her."

This process helps the NT partner see the

"coldness" as a fear response, fostering compassion rather than

resentment.

6. Lived Experiences: The View from Both Sides

The statistical and theoretical data is illuminated by the

qualitative reports of partners living in these marriages.

6.1 The NT Perspective: The "Cheerleader" and

the "Manager"

NT partners often describe a dynamic where they function as

the "social secretary," "emotional interpreter," and

"household manager" for the couple. They report a sense of

"affective deprivation," feeling that their partner loves them

intellectually but not visibly.

- The

"Texture Eater" Example: One NT wife describes how her

autistic husband helps her navigate food aversions at

restaurants. This illustrates that when the NT partner has specific

needs, the Autistic partner can be incredibly supportive if the need is

clear and actionable.

- The

Grief Gap: An NT partner describes grieving a death and their

autistic spouse getting angry at their sadness because it disrupted the

routine. This highlights the painful disconnect when negative affect is

involved.

6.2 The Autistic Perspective: Confusion and Overwhelm

Autistic partners frequently describe feeling like they are

constantly failing a test they didn't study for. They report loving their

partners deeply but being baffled by the "emotional logic" required

of them.

- The

"Attack" Perception: Autistic husbands often perceive

their wives' expressions of feelings as direct criticism. If the wife

says, "I feel lonely," the husband hears, "You are failing

at your job as a husband." This triggers a defensive/systemizing response

("I am here every night, how can you be lonely?"), which

invalidates the wife's feeling.

- Fear

of Getting it Wrong: Many autistic partners withdraw not because

they don't care, but because they are terrified of saying the wrong thing

and making the situation worse. Silence feels safer than

error.

7. Conclusion: From Deficit to Translation

The research definitively debunks the myth of a global

"empathy deficit" in autism. Autistic individuals in marriages

possess robust affective empathy and often a deep, loyal commitment to their

partners. The dysfunction in ASD/NT marriages is rarely a lack of love; it is a

lack of translation.

The "Double Empathy Problem" clarifies that the

neurotypical partner contributes to the disconnect by rigidly adhering to

neurotypical norms of communication (implicit, non-verbal, face-to-face) and

pathologizing the autistic partner's divergent style (explicit, parallel,

action-oriented).

Successful ASD/NT marriages do not require the autistic

partner to become neurotypical. They require a "Third Culture"

approach:

- Acceptance

of Neurological Reality: Acknowledging that alexithymia and

sensory processing differences are physiological, not behavioral choices.

- Explicit

Communication: Replacing hints with direct requests and

agreed-upon scripts.

- Redefining

Intimacy: Validating parallel play, info-dumping, and acts of

service as legitimate forms of connection.

- Trauma

Reduction: Distinguishing between malicious silence and

protective shutdowns to stop the cycle of pursuit and withdrawal.

By moving away from the deficit model and toward a model of

cross-neurotype accommodation, couples can bridge the "empathy gap"

not by changing who they are, but by learning to speak each other's language.

The challenge is significant, but the evidence suggests that with the right

interpretive tools, the "empathy deficit" dissolves into a manageable

difference in emotional expression.

7.1 Cognitive Empathy in Depth: The Mechanics of

"Mind-Blindness"

While the distinction between cognitive and affective

empathy is established, deeper investigation into cognitive empathy—often

termed "mind-reading" or "mentalizing"—reveals the specific

mechanical failures that occur in neurodiverse interactions. The deficit in

cognitive empathy is not an inability to care, but a processing error in

predictive coding.

Research indicates that neurotypical brains operate on a

predictive model, constantly simulating the likely thoughts and intentions of

others based on minute cues. In contrast, autistic brains often process

information bottom-up, relying on explicit data rather than probabilistic

simulation. This means an autistic partner does not "automatically"

intuit that a sigh means sadness; they must be told, "I am sighing because

I am sad."

This "context blindness" extends to situational

awareness. An NT partner might expect their spouse to understand that a crowded

party is not the time to discuss finances. The autistic partner, focusing on

the content of the discussion rather than the context,

may not perceive the social impropriety. This is often mislabeled as

selfishness or lack of tact, when it is actually a failure of cognitive

integration—the inability to simultaneously process the verbal message and the

environmental context.

Furthermore, studies using the "Eyes Task"

(reading emotion from eyes alone) show that autistic individuals score

significantly lower than controls. This suggests that the primary data

channel for NT empathy—the eyes—is often inaccessible or overwhelming for

autistic people. Relying on eye contact to convey emotional urgency to an

autistic partner is, therefore, neurologically

counterproductive.

7.2 The Role of Gender in Empathy Assessments

The "empathy deficit" myth is heavily gendered.

Diagnostic criteria for autism were largely developed based on male

presentations, leading to a "male-centric" view of autistic

traits. Autistic women often present differently, utilizing

"camouflaging" or "masking" to simulate neurotypical social

skills, including empathy.

Research shows that autistic women often score higher on

empathy measures than autistic men, but at a high psychological cost. They

may intellectualize empathy, studying social rules like a science to avoid

detection. In a marriage, an autistic wife might be hyper-attentive to her

partner's needs, not out of intuitive flow, but out of anxiety-driven

vigilance. This "compensatory empathy" can lead to burnout, where the

autistic partner suddenly withdraws after years of apparent high functioning,

leaving the NT partner confused.

Conversely, the "systemizing" nature of male

autism often aligns with traditional masculine stereotypes (the stoic

provider), masking the neurological basis of the behavior until the emotional

demands of marriage expose the deficit in reciprocal

vulnerability.

7.3 Systemizing and the

"Input-Operation-Output" of Care

The "systemizing mechanism" (SM) is a key concept

in understanding autistic cognition. It is the drive to analyze, understand,

and construct systems based on input-operation-output rules. In the

context of relationships, this is often misunderstood as cold

logic.

However, for the autistic partner, systemizing is caring.

If a partner is distressed (input), the autistic mind seeks an operation (fix)

to produce a new output (relief). This is a deeply empathetic act in the

autistic framework. The disconnect occurs because neurotypical empathy often

prioritizes validation (sitting with the distress) over resolution (fixing

the distress).

When an autistic partner offers a solution, they are

engaging their highest cognitive faculty to aid their loved one. Rejection of

this solution ("I don't want you to fix it, I just want you to

listen") can be baffling and hurtful to the autistic partner, who

perceives their effort to help as being rebuffed. Understanding this

"logic as care" paradigm is essential for reinterpreting the

"coldness" often attributed to autistic spouses.

7.4 The Physiology of Empathy: Mirror Neurons and Sensory

Overload

The neurological underpinnings of the empathy gap may

involve the mirror neuron system (MNS), which fires both when an individual

performs an action and when they observe someone else performing it. Some

theories suggest a "broken mirror" in autism, but recent evidence

points instead to a "hypersensitive mirror".

The intense sensory processing issues common in autism mean

that emotional signals from others can be physically painful. A partner's

crying might not just be sad; it might be audibly piercing and visually

chaotic. The "shutdown" response is often a way to block out this

sensory assault. Thus, the lack of empathetic response is not a lack of

feeling, but a physiological incapacity to remain present in the face of

overwhelming sensory data.

This is supported by the "Empathy Imbalance

Hypothesis" (EIH), which argues that autistic people feel too much affective

empathy, leading to distress and withdrawal. The "cold" exterior

is a shield against a "hot" interior. This reframing changes the

therapeutic goal from "teaching empathy" to "managing overwhelm"

so that innate empathy can be expressed safely.

7.5 Relational Ripple Effects: The Parenting Dynamic

The empathy disconnect often reaches a crisis point when the

couple has children. Parenting requires high levels of rapid, non-verbal,

intuitive empathy. An autistic parent might struggle with the chaotic,

irrational nature of a toddler's emotions, leading to withdrawal or rigid

disciplinarianism (systemizing the child).

The NT partner then becomes the "default parent"

for emotional labor, deepening the "Cassandra" dynamic of isolation

and burden. However, autistic parents also bring unique strengths:

consistency, loyalty, and a lack of judgment that can be deeply stabilizing for

older children. Recognizing these different parenting "love

languages" is crucial for family cohesion.

7.6 Future Directions: From Pathology to Neurodiversity

The shift from the "deficit model" to the

"neurodiversity model" has profound implications for the future of

ASD/NT relationships. As society moves away from viewing autism as a tragedy

and toward viewing it as a variation, the pressure on autistic partners to

"pass" as neurotypical may decrease.

This cultural shift allows for new models of partnership

where difference is negotiated rather than pathologized. It encourages

"neuro-mixed" couples to invent their own social contracts,

unburdened by standard expectations of how a marriage "should"

look. The rise of neuro-affirming therapy and community support groups

(like those for "Cassandra" partners that focus on understanding

rather than blaming) signals a hopeful trend toward integration and mutual

respect.

Ultimately, the "Empathy Deficit" myth is a relic

of a time when difference was equated with brokenness. The reality is far more

complex, challenging, and potentially rewarding. By embracing the "Double

Empathy" framework, couples can move from a war of neurologies to a

collaboration of minds.

==> Cassandra Syndrome Recovery for NT Wives <==

|

| Mark Hutten, M.A. |

Pick Your Preferred Day/Time

Available Classes with Mark Hutten, M.A.:

==> Cassandra Syndrome Recovery for NT Wives <==

==> Online Workshop for Men with ASD level 1 <==

==> Online Workshop for NT Wives <==

==> Online Workshop for Couples Affected by Autism Spectrum Disorder <==

==> ASD Men's MasterClass: Social-Skills Emotional-Literacy Development <==

Individual Zoom Call:

==> Life-Coaching for Individuals with ASD <==

Downloadable Programs:

==> eBook and Audio Instruction for Neurodiverse Couples <==