Why Some Neurotypical Wives with Childhood Trauma Gravitate Toward Emotionally Unavailable Partners

Why Some Neurotypical Wives with Childhood Trauma Gravitate Toward Emotionally Unavailable Partners

What “neurotypical” means here

In this article, “neurotypical” (NT) refers to people whose neurological development and information-processing align with common societal expectations—often contrasted with “neurodivergent” conditions such as autism or ADHD. It’s a descriptive, non-clinical term used in discussions of neurodiversity to denote typical neurological development. Merriam-Webster+1

How childhood trauma shapes adult relationship choices

Childhood trauma—whether neglect, emotional unavailability at home, maltreatment, or chaotic caregiving—can leave enduring imprints on how people understand love, safety, and closeness. A growing body of research links early adversity to insecure attachment patterns, difficulties with emotion regulation, and lower relationship satisfaction in adulthood. These effects often operate through attachment mechanisms: when a child’s emotional needs were inconsistently met, the adult may anticipate rejection, cling to ambivalent signals, or feel most “at home” in relationships that echo old patterns. ScienceDirect+2Taylor & Francis Online+2

Why emotionally unavailable partners can feel so compelling

Several complementary psychological frameworks help explain this pull:

-

Attachment dynamics. People with anxious attachment are often drawn to avoidant (emotionally distant) partners. The intermittent responsiveness of an avoidant partner mirrors early experiences of inconsistent care, which can intensify pursuit in the hope of finally earning reliable connection. Clinicians describe a “dance” between anxious and avoidant styles that can initially feel magnetic but ultimately keeps both partners stuck. Columbia Psychiatry+1

-

Repetition compulsion & reenactment. Early psychoanalytic ideas—now translated into modern, testable concepts—suggest we sometimes repeat familiar relational patterns to master them. When trauma is unprocessed, we may unconsciously select scenarios that recreate the old wound, seeking a different outcome this time. In relationships, this can look like gravitating toward partners who withhold, criticize, or stay distant—because it feels familiar and offers the illusion of “fixing” the past. Medical News Today+1

-

Schema theory. Schema therapy research identifies early maladaptive schemas—deep, organizing beliefs about self and others—such as emotional deprivation (“my needs won’t be met”) or abandonment. These schemas predict lower relationship satisfaction and can bias partner choice toward those who confirm the schema (e.g., someone who is emotionally unavailable), thereby keeping the belief intact. Recent studies continue to link emotional-deprivation and abandonment schemas with relationship dissatisfaction and partner dynamics. Frontiers+2PMC+2

-

Intermittent reinforcement & intensity mistaken for intimacy. When affection comes in unpredictable bursts, the nervous system may equate intensity with love. That “spark” at the beginning of a hard-to-get relationship can be misread as compatibility rather than an activation of an old pattern. Popular writing captures this phenomenon, but the underlying mechanism is consistent with attachment and learning principles. Columbia Psychiatry+2Psychology Today+2

Realistic composite examples (anonymized)

-

Case A: “Emily, 36.” Emily grew up with a parent who was often preoccupied and emotionally distant. As an adult, she feels a surge of chemistry with partners who are hard to read. Jason, her current partner, is kind but shuts down when stressed. Emily finds herself working harder for closeness—texting more, anticipating needs—while telling herself, “If I’m patient enough, he’ll finally open up.” The cycle mirrors her childhood hope that consistency would arrive if she performed well enough. (Attachment anxious–avoidant pattern; emotional-deprivation schema.) Columbia Psychiatry+1

-

Case B: “Natasha, 42.” Natasha’s early home involved unpredictable affection—warmth on some days, withdrawal on others. She later chooses partners who are thrilling but inconsistent. After a caring week, they grow aloof, which spikes her anxiety and drives pursuit. The on-off reinforcement keeps her invested despite clear distress—an example of reenactment of intermittent care. (Repetition compulsion; attachment activation.) Medical News Today+1

-

Case C: “Renee, 29.” Renee internalized a belief that her emotional needs are “too much.” She dates partners who say they prefer “low-drama” relationships and subtly criticize emotional expression. Renee then suppresses her needs and feels unseen—confirming the schema that closeness isn’t available to her. (Emotional-deprivation schema.) Frontiers

Practical steps for NT women seeking healthier relationships

-

Name the pattern in compassionate language. Reframe “I’m broken” into “My nervous system learned closeness as unpredictable.” That shift reduces shame and opens space for change. Evidence shows that understanding attachment tendencies helps people choose and build more secure relationships. Columbia Psychiatry

-

Track cues of avoidant dynamics early. Watch for consistent canceling, irritation with emotional talk, or idealizing independence while devaluing interdependence. It’s not about pathologizing a partner; it’s about checking for fit with your needs for responsiveness and repair. (Attachment-informed screening.) Columbia Psychiatry

-

Practice “earned security” skills.

-

Co-regulation: Use grounding, paced breathing, or a supportive call before big relationship talks so the body isn’t driving the bus.

-

Boundaried bidding: Ask directly for specific connection (“Could we set aside 15 minutes after dinner to check in?”) and notice whether the pattern is consistency or evasion.

-

Reality testing: Keep a small log of bids and responses to counter confirmation bias from old schemas. (Schema/attachment-informed strategies supported by the broader link between early adversity, emotion regulation, and adult relationship functioning.) PMC

-

-

Therapies with evidence for trauma. Consider trauma-focused approaches (e.g., EMDR) and attachment-informed therapies. Reviews and guidelines report moderate to strong evidence for EMDR in reducing trauma symptoms, which can indirectly improve relationship patterns. PTSD.va+2PMC+2

-

Choose partners who demonstrate secure behaviors. Look for people who repair after conflict, tolerate emotional conversation, and follow through reliably. Early secure signals often feel “quiet” if you’re used to intensity—give them time before dismissing them as “no chemistry.” (Attachment education.) Columbia Psychiatry

-

Build secure supports beyond the partner. Trauma’s effects are buffered by warm, responsive relationships and community. Enlist trusted friends, support groups, or a therapist so your entire attachment load doesn’t rest on one person. PMC

Resources (credible and accessible)

-

Find a trauma-informed therapist: APA Psychologist Locator and National Register “Find a Psychologist.” APA Psychologist Locator+1

-

Learn about attachment patterns: Columbia Psychiatry overview on attachment styles in relationships. Columbia Psychiatry

-

Understand EMDR and trauma treatment options: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (PTSD) clinician summary. PTSD.va

A compassionate takeaway

If you recognize yourself in these patterns, it doesn’t mean you’re doomed to repeat them. It means your nervous system learned rules for love in an environment that wasn’t consistently safe, and it has been doing its best to protect you. With awareness, support, and (when needed) trauma-focused therapy, many NT women discover they can choose differently—moving from the chase for emotional availability to relationships where responsiveness, repair, and mutual care are the norm. Research increasingly shows that when early injury is acknowledged and tended to, adult relationships become more satisfying and secure. PMC

Language note: “Emotionally unavailable” is a descriptive label, not a diagnosis. People may be distant for many reasons (stress, culture, neurotype, depression). The goal is not to stigmatize anyone, but to help readers make choices that align with their needs for emotional safety and mutuality.

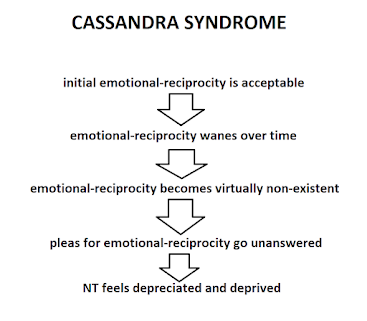

==> Cassandra Syndrome Recovery for NT Wives <==

|

| Mark Hutten, M.A. |

Pick Your Preferred Day/Time

Available Classes with Mark Hutten, M.A.:

==> Cassandra Syndrome Recovery for NT Wives <==

==> Online Workshop for Men with ASD level 1 <==

==> Online Workshop for NT Wives <==

==> Online Workshop for Couples Affected by Autism Spectrum Disorder <==

==> ASD Men's MasterClass: Social-Skills Emotional-Literacy Development <==

Individual Zoom Call:

==> Life-Coaching for Individuals with ASD <==

Downloadable Programs:

==> eBook and Audio Instruction for Neurodiverse Couples <==